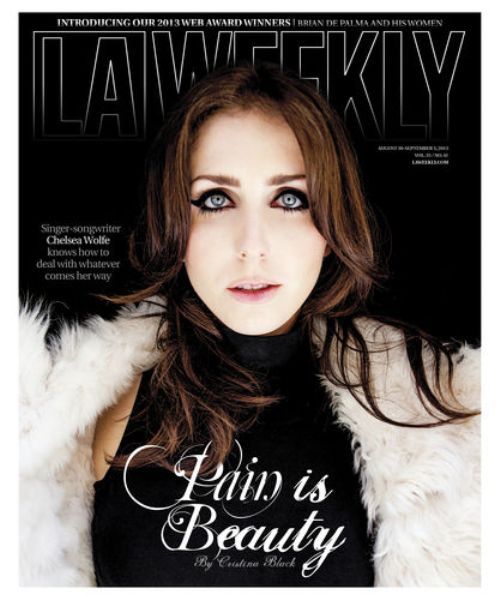

Chelsea Wolfe is looking at a picture of herself. It’s on the cover of the deluxe vinyl version of her new album, which is out this week. She’s seeing it now for the first time, sitting at the dining room table at the Echo Park home of her record label, Sargent House. The photo shows her standing in a bright spotlight against a black background, attired in a scorching red vintage dress. She wears dark lipstick and holds a piercing gaze through black-lined eyes, yet her shoulders are slightly hunched, her pale arms clasped tightly to her midriff as she clutches her elbows with the opposite hands. It’s the body language of a strange, tall girl at a middle-school dance, just after her growth spurt. “There I am in the spotlight,” she says between drags of a cigarette, “looking a little uncomfortable.”

photo by Kristin Cofer

The shot is well chosen, least of all because it’s gorgeous; it also perfectly encapsulates this moment in Wolfe’s career. It depicts the downtown dweller emerging from her shadowy goth-folk stage and forging her status as a sophisticated figure with a crystallized point of view, succinctly spelled out in the album’s title, which floats in crimson, doom-metal typeface above her black-maned head: Pain Is Beauty.

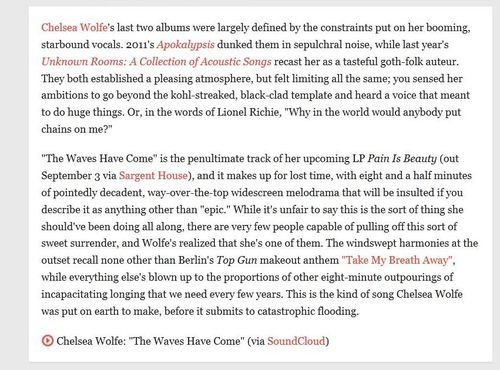

Since the release of her 2010 debut album, The Grime and the Glow, Wolfe, has attracted a small army of fans in the United States and Europe — including a random smattering of celebrities such as John Cusack, Dave Navarro and Sasha Grey — with some of the most dramatically gloomy music coming out of Los Angeles right now. Her canon is all emotion, with cryptic lyrics full of yearning, focused on death and devastation, set against haunted, heavily reverbed sound scapes that range from guitar strums and electronic samples to found sounds and disturbed screeching.

this photo and LA Weekly cover image by Ryan Orange

Her second album, last year’s Apokalypsis, begins with the unnerving track “Primal/Carnal,” which could easily be used on loop as sound effects for an arty haunted house. But Wolfe always includes a dab of hope in all that unholiness, for contrast. “Life is always bringing shit our way,” she explains. “When we deal with it, we come out wiser and stronger and have a more beautiful outlook. Pain becomes beauty.”

The new album seals her vision with tales of tormented love set against impossible conditions, including titles like “Destruction Makes the World Burn Brighter” and “The Waves Have Come,” a selection based on a man widowed by the 2011 tsunami.

Wolfe points out that the red dress she wears on the album’s cover represents volcanic lava. “I was thinking about how nature can just, like … ” she trails off for a second, overwhelmed by her own thoughts, then refocuses her ice-blue eyes. “We think we have everything under control, but we really don’t,” she says. “There could be an earthquake right now.”

Despite the darkness in her music, Wolfe is kind, almost light, in person. She speaks warmly about the things that matter most to her — art, nature, love — but remains cagey about personal details, and her lyrics offer few concrete clues about her own life story.

“I think a lot of the album, thematically, is about idealistic love,” she says. “The Warden,” for example, is an alternate ending to 1984, where the imprisoned protagonist refuses to give in to torture, agonizing until his last breath to protect his lover.

On “Sick,” Wolfe reveals the benefit of languishing inside a difficult relationship. “This suffering brings me closer to you/and time is broken and moves slow,” she sings.

With every ghostly wail, she exposes an unwavering truth — love is hard. “When you’re really in love with someone, it’s not always easy,” she says, careful not to wreck her mystery with any real specifics. “It’s so beautiful and it’s so fucked up.”

She’s always been this intense. As a little girl, Wolfe sought tragedy obsessively. “My parents thought there was something wrong with me because I would watch the world news for hours and cry about all the shit people were going through,” she recalls earlier, over drinks at downtown trip-hop haunt Pattern Bar. “I just wanted to feel it all and understand the world beyond my own little realm.”

Growing up in Sacramento, Wolfe began writing sad songs in her country-musician father’s studio around age 9, but up into adulthood she stayed away from the stage. After dabbling in various university studies and career starts, by the late 2000s she’d let her friends convince her to focus on music.

Originally a painfully self-conscious performer who often appeared onstage with a black veil over her face, Wolfe eventually overcame her fears, embracing ethereal fashion and emphasizing her own natural height (she’s 5 feet 9 inches) with teetering heels. “I decided if I’m going to take this seriously,” she says, “I should dress up for work and give it my all.”

Last year, she became even more vulnerable to her listeners with her acoustic collection, Unknown Rooms. Previously scattered across the Internet, the album of stripped-down “orphan” recordings was her first release on Sargent House, the local label owned by entertainment entrepreneur Cathy Pellow.

“She was always lumped in with these droney-ass bands,” Pellow says of Wolfe’s branding, citing the cover of Apokalypsis, which features a medieval-style photo of Wolfe with her eyeballs whited out. “I wanted to open the doors to people who would have written her off as creepy and scary, so they could hear the purity and uniqueness of her voice.”

The pastoral love song “Flatlands,” with its spare guitar and gentle string arrangement, made its way around the Internet via a video collaboration with Converse and Decibel magazine, setting the scene for the more electronic-oriented Pain Is Beauty. By the time the new album’s single, “The Warden,” hit Soundcloud in June, its industrial-clubby beat seemed like a natural expansion on Wolfe’s varied sonic palette.

“I think about the lifespan of an artist,” says Pellow, who represented film talent in New York City before moving to L.A. in the mid-2000s to build Sargent House around her personal passion for progressive rock bands like Russian Circles, Deafheaven and Hella. “It was, like, let’s let a lot of people who don’t listen to heavy music find out Chelsea’s not that heavy. This way, down the road, she can do whatever she wants.”

Sargent House sits at the edge of Elysian Park. The historic, Spanish-style mansion houses the label’s offices, a small studio and a window-encased alcove used primarily as the performance space for “Glass Room Sessions,” the series of live acoustic performance videos in which Wolfe was featured last year.

Pellow encourages a party like atmosphere around creative and business collaboration. Tonight, the gathering includes in-house producer Chris Common, new signee Emma Ruth Rundle, Wolfe and her bandmate and co-producer Ben Chisholm. Wolfe and Chisholm chat about their recent video shoot with director Mark Pellington (who shot the iconic video for Pearl Jam‘s “Jeremy,” among many others), before Wolfe ducks into the studio to sing on Rundle’s upcoming album.

Wolfe at various times calls herself “shy,” “not outgoing” and “a bit of a loner.” She’ll claim she isn’t an L.A. artist, she isn’t an anything artist, and she’s never felt the need to fit into any scene. Here, at least, she seems at home, which might make it a bit easier to step into the limelight and face unknown heights of success and scrutiny.

“Life is really hard,” she says. “You have to persevere.”

It’s not clear if she’s talking about herself or the entire history of humanity. Maybe it’s both.

By Christina Black