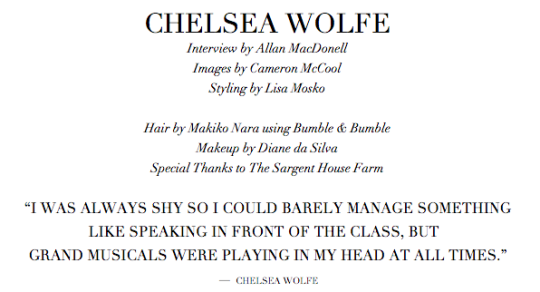

Chelsea Wolfe interviewed by Allan MacDonnell for Issue Magazine

With a tonal darkness that borders on infernal, Chelsea Wolfe has been building and experimenting with nearly every genre of music since the age of nine. The California-born singer-songwriter’s music is now creeping into the mainstream with her 2013 release Pain Is Beauty, while holding tight to her underground following. Her track “Feral Love” was featured in HBO’s Game of Thrones, and she collaborated with director Mark Pellington (The Mothman Prophecies,Arlington Road) for her longform music video-film Lone. Her newest album,Abyss, was recorded in Dallas with producer John Congleton (Swans, St. Vincent) and takes a quote by designer Yohji Yamamoto as its talisman: “Perfection is ugly. Somewhere in the things humans make, I want to see scars, failure, disorder, distortion.”

As a former editor of Hustler magazine and author of Punk Elegies, a memoir about the birth of the ’70s LA punk movement, Allan MacDonell has a comprehensive outlook on the punk rock music scene. Here, MacDonell discusses Wolfe’s career, the theatrical elements of her music and her creative process.

Allan Macdonell: How, if at all, does Sacramento figure in your presentation?

Chelsea Wolfe: Living there gave me the time and the platform to experiment with music. I’d been writing and recording songs since I was a little kid living in the oldest part of a suburb outside of Sacramento. When I was around 20, I moved downtown, got a job and tried to play music. I was not very good for a long time. I would play two or three songs, get freaked out and run off stage. I was writing songs that were so autobiographical they made me feel physically sick, so I decided not to write about my personal life anymore and to write about things outside of myself. Then I left [Sacramento] for a while with a good friend and great performance artist Steve Vanoni. He taught me about life and art and gave me a chance to start playing music in front of new and accepting audiences. I followed a tour of performance art shows in Europe and would play at the end of the night. Then I came back home to Sacramento and recorded The Grime and The Glow; then moved to LA soon after.

AM: Both your parents are musicians, and your father in particular encouraged and influenced your musical self-education. Can you speak to the important part your parents played in your evolution as an artist?

CW: My dad is a musician; he was in a country band while I was growing up. My mom doesn’t play music but is a very artistic person and turned me on to some good music—Bonnie Raitt, Joni Mitchell, Neil Young. Both of them were supportive of me playing music. My dad passed down guitars, pedals and amps to me, and my mom always pushed me to keep trying. Unfortunately, for some reason there was a voice in my own head telling me I wasn’t good enough to do this and be up in front of people. So I tried going to different colleges and finding a new path, but in the background I was always playing music. The fact that I finally gave in and pursued playing music full time is really the result of family and friends and people encouraging me—pushing me to record and put my songs out in the world.

AM: What’s the most unsettling comparison someone has made regarding your music?

CW: I think it’s annoying for any artist when a journalist states that you’re influenced by an artist who you’ve never listened to or been into. Even if that artist is great, it’s still just weird.

AM: Are you a used-record shopper? If so, any favorite places to search?

CW: If we have a day off on tour and a city has a cool record store, my bandmates usually want to go there so I’ll go too. I’m never that drawn to record stores, but once I’m there, it’s kind of mesmerizing to wander through. I like the classical section at Amoeba.

AM: Virginia Woolf said: “Money dignifies what is frivolous if unpaid for.” How important to is you making a living as an artist?

CW: I am making a living as an artist, and it’s pretty crazy to me still. I feel really lucky and very thankful. But I also live pretty simple. I live on the outskirts, in the mountains—in part to get away from all the noise, but it’s also much more affordable out there. I can have a house with a yard for the price of maybe one bedroom in some cities.

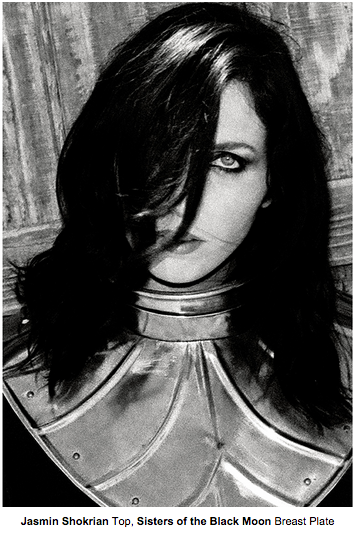

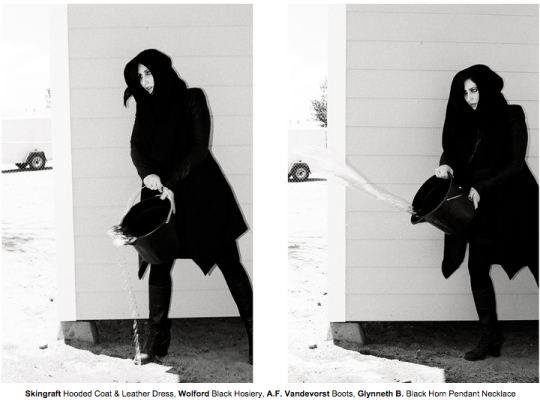

AM: Do you consciously produce theatrical elements in your work?

CW: I’ve had an affinity for the dramatic since I was a kid. I was always shy so I could barely manage something like speaking in front of the class, but grand musicals were playing in my head at all times. I don’t think that making my music dramatic is a conscious decision. I think it just happens.

AM: In your filmmaking collaborations, what are the challenges and rewards as an artist in melding visual themes to your music?

CW: It’s very challenging. I struggle with photo shoots even. I can only handle like an hour of it and then I’m a bit done. But with filming you’re doing a lot more hours and there’s a lot more people involved, so it really broke me down when I was filming Lone—this series of emotional, surreal music videos with director Mark Pellington. It broke me down to the point that I was intensely real and vulnerable on screen, and it was hard for me to watch that later, to be honest. But at the same time I think it helped me to sort of accept myself more.

AM: How do you overcome self-doubt?

CW: It’s hard for me to get onstage sometimes, but I have to just say “fuck it” and go.

AM: After working alone, what adjustments do you make to work collaboratively?

CW: I go back and forth between the two very often. At this point, this project has become very collaborative even though it started as a solo project. When I write alone, I try to just set my mind and emotions loose and write in a very instinctual way. Other times my bandmate and main collaborator Ben (Chisholm) will be working on a song, and I’ll latch onto a certain part and encourage him to expand on it, and the song sort of grows from there.

AM: Can you compare the emotional experience of recording to the emotional experience of playing live in front of an audience?

CW: By the time I get to the studio I’ve spent months or years writing, curating and refining the songs for whatever album I’m going in to work on. So once I’m there, I’m pretty utilitarian about things and want to work and move the songs forward. My favorite part—and the part that causes me the most turmoil—is mixing, piecing all the elements together at the very end. I’m pretty particular about little sounds and how things flow, and I can make myself crazy about it. But it’s all very insular—just this intense experience you have with building for a month or whatever—and then you come out of it with a finished piece. Playing live in front of people, you’ve got to pull yourself together in order to fall apart again. Maybe it doesn’t make sense, but you have to know the songs really well in order to really lose yourself inside them. And you have to feel really strong and confident in order to go out on stage and become a broken, real person in front of people. At least that’s how it is for me.

AM: Have you been mentored in navigating the business aspects of your career? How does an artist learn that skill?

CW: I have a great manager. I never really understood what a real or good manager did before I met Cathy Pellow. Her goal has always been to help me grow as an artist and be a career artist so that, hopefully, I can still be releasing music and playing when I’m grey-haired. It’s not that she tries to sway me one way or another, but she’s always there to guide as we navigate a path that is always kind of morphing and surprising us.

AM: Do you ever hear a song and think, “Man, I’d like to have written that”?

CW: I think the Iceage song “Forever” is really beautiful. When I first heard it I definitely had a sense of how did they do that?

AM: Has being “unclassifiable” helped or hurt you in reaching your audience?

CW: I imagine that it has helped. We’ve been accepted in many different worlds. I feel grateful for it.

AM: Who among your contemporaries isn’t being heard as widely as they should be?

CW: Screature. They just released their second album, Four Columns. They’re hometown friends from Sacramento who blow me away with how multi-talented and rad they all are, and their band is really fucking good. I want more people to hear them because I think other people will enjoy them too.

AM: Is the range of music you listen to for pleasure as wide and varied as the range of styles you write and play?

CW: Even more. Most of the time I’ll put on Scientist records for hours, and that puts me in a trance. Then I’ll listen to Wardruna or maybe Aphex Twin depending on my mood. I make mixes on Spotify, kind of in themes—I have one that is Tricky, soundtrack music from Werner Herzog films, John Fahey, Colleen, Abner Jay. I find familiar things in all different styles of music.

AM: How big would your ideal audience be for a live performance?

CW: Ideally it’s great when the audience is full of people who like your music and just want to be there with you to experience it. Hopefully it’s in a theater or hall with some nice sound and old feelings and good energy. I’d say all that comes before audience size.